Savage remembered as a trailblazer

GREEN COVE SPRINGS— Clay County and City of Green Cove Springs leaders recognized the work of Harlem Renaissance artist Augusta Savage during a ceremony dedicating a historical marker in her honor.

Green Cove Springs Mayor Matt Johnson, City Manager Steve Kennedy, Clay County Commissioner Kristen Burke and others spoke at the marker’s dedication, followed by an open house at the Augusta Savage Arts and Mentoring Center.

Thanks for reading Clay Civic! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

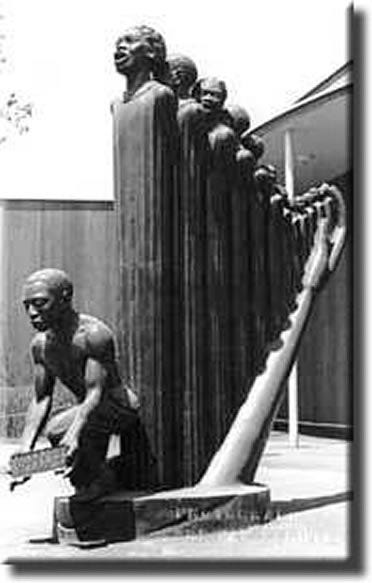

In the 1930s, the Green Cove Springs native was a well-known teacher, sculptor, and community arts leader. Two of her most recognized works are “The Harp,” an exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair and “Gamin” (French for “street urchin”), which many consider to be her finest accomplishment.

Graven images

Clay County Historic Preservation Board Member Jerry Casale told the audience at the Sept. 19 dedication ceremony that Savage first began to fashion ducks and other animals from the clay at the Clay County Brickworks down the street from her home.

The seventh of 14 children of Edward and Cornelia Fells, Augusta immediately encountered opposition to her passion from her father. The Methodist pastor opposed his daughter’s art based on the biblical prohibition against creating graven images.

“That was a problem she had to overcome,” said Casale, “probably by sneaking around and doing it anyway.”

Casale said another obstacle for the teenage sculptor to overcome was safely obtaining sculpting material from the deep and dangerous clay pit within the brickwork’s property.

“Eventually, the workers decided just to hand her the clay because they were afraid of her falling in,” he said.

In 1908, when she was 15, Savage married John Moore. The couple had their first child the following year.

Casale said Moore disappeared from the family record in 1910.

“It’s usually reported that he died and she was widowed and so forth,” said Casale, “but the fact is, we don’t yet really know, and maybe we never will.”

The family then moved to West Palm Beach, where Savage begged for clay from a local potter.

“Once again, she entered some competition at a state fair, and her animals and other creatures were such a hit that she won a prize,” he said.

Casale added that Savage found some commercial success with her work, selling her art and landing a teaching job after impressing the local school superintendent with her work.

While in West Palm Beach, the young artist met and married James Savage, whom Casale described as a regular working guy.

“Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,”

He said her professional ambition superseded her commitment to Savage, so she moved to Jacksonville to advance her career.

While family members cared for her daughter Irene, Savage sculpted portraits of Jacksonville’s black elite.

While in Jacksonville, Savage met brothers James Weldon Johnson and John Rosamond Johnson, composers of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” widely regarded as the Black National Anthem.

The Johnsons encouraged Savage to relocate to New York, which she did, securing a spot at the Cooper Union School of Arts in the 1920s.

It was in New York that she achieved national fame and attracted benefactors that supported her financially while she studied at the school.

Casale said Savage’s success in New York led to a scholarship at the Fontainebleau School in France. However, some of her fellow passengers on the trans-Atlantic liner objected to sharing space with a black woman, and she was eventually removed from the trip.

Savage responded by going public with the slight and gained support in New York’s newspapers.

Casale said Savage displayed some public relations talent in addition to her skill as a sculptor, always portraying herself as 10 years younger than her actual age and never mentioning her husband or daughter.

“So that made it more appealing, and they ran with it,” Casale said of the media. “So, if you try to read about her situation in 1923, that’s what you’ll see. The only place they got that was from Augusta herself. If you don’t have a publicity agent, you have to do it yourself.”

1939 World’s Fair

Savage eventually reached France and saw success there, winning awards and accumulating knowledge of her art form.

Casale said Savage got the most exposure in Europe during the Colonial Exposition of 1930-1931.

He added that while Savage could have been offended at the exposition, which celebrated the exploitation of Europe’s African colonies, the artist instead dealt with the situation she found herself in and did her best with it. Casale said that attribute fostered Savage’s resiliency.

Returning to New York in the middle of the Great Depression, Savage had trouble securing funding for an art school she wanted to establish.

She was hired as the first director of the Harlem Center of Art, a position she held until 1937, when she was commissioned to create a massive sculpture for the 1939 World’s Fair.

The piece, called “The Harp,” depicted a group of 12 black singers arranged in the shape of a harp. Each singer represented a group of strings on the instrument.

The sculpture was inspired by the work of Savage’s old Jacksonville friends: the Johnson Brothers, and their anthem, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.”

While postcards were made from the image of the sculpture, the original work was bulldozed after the fair.

Teaching mission

After the fair, Savage tried again to establish an art school, but in the midst of the depression, she could not secure funding.

Finally, a stalker forced her to leave the city, and she retreated to the town of Saugerties, on the Hudson between New York and Albany. There she found work in a mushroom factory but continued her educational mission by finding students to teach sculpting and painting.

“She never lost sight of her teaching mission,” Casale said, “and it was kind of poignant that in the end, she talked about teaching as her main legacy. She taught the next generation of aspiring artists, especially black painters and sculptors who later made their own name for themselves.”

Casale said Savage lived out the remaining years of her life in obscurity, primarily because the art world had moved onto abstract and primitive art, while Savage stubbornly stuck to the classical style.

“Classical art was for the ordinary folk,” he said. “The people with the money and the patronage had moved on to abstract art and primitive art.”

Casale said Savage stuck with the classical form because she wanted to depict African Americans in her work, giving them dignity and honor.

He attributed her willingness to stick to her core values as another strength.

The spirit of Augusta

Henrietta Francis, President of Friends of Augusta Savage, added that the artist lived a life she was told she could not have.

“She had a real determination and sense of her own talent and a refusal to be denied,” Francis said.

Francis added that when Savage built her career, Jim Crow laws suppressed African Americans, and racism and sexism were at their peak.

“And here comes this little black woman from Green Cove Springs, Florida, who had the nerve and the audacity to say, ‘Look, I can do this,’” she said.

Francis acknowledged Savage’s early obstacles to her career: her father’s opposition to her art, her marriage at age 15, and a child one year later.

“But she still had this love, and she still had this innate talent,” Francis said. “She refused to be denied.”

Francis also recognized the importance of the site now housing the Augusta Savage Arts, Community, Museum and Mentoring Center.

“She was not only born here, which is reason enough,” Francis said, “but this is the site of Dunbar High School: the only black high school in Clay County, so this means a lot for a whole lot of people.”

Francis said she hopes every student who walks through the center’s doors will capture the spirit of its namesake.

“The main thing that I would like for you to capture from Augusta is her spirit,” Francis said, “her undeniable persistence, her refusal to give up, her knowing that she had the ability and that she could, and she did.”

“That spirit of Augusta is what we want each student that walks through that door to capture,” she continued, the spirit of ‘I can do it.’ The spirit of, ‘I won’t be denied.’ The spirit of ‘I will not be held down.’”